As a graduate student navigating the complexities of bioadhesion research, Angelico Obille recognizes the importance of effective communication, both within the scientific community and to the broader public. His recent participation in the 3MT competition served as a testament to his dedication to bridging the gap between technical expertise and accessible language, a skill he honed through years of interdisciplinary study. Beyond his academic endeavors, Angelico’s love for music, cultivated since childhood, serves as both a creative outlet and a metaphorical lens through which he views the scientific process. With a deep understanding of the interconnectedness of art and science, Angelico brings a unique perspective to his research, drawing inspiration from nature’s own engineering marvels to develop innovative solutions for medical adhesion. Furthermore, Angelico’s advocacy for mental health awareness underscores his holistic approach to graduate education, emphasizing the importance of support networks and sustainable routines in navigating the challenges of academia. Through his diverse interests and unwavering commitment to inclusivity and accessibility, Angelico Obille exemplifies the next generation of scientific leaders, poised to make a meaningful impact both within and beyond the laboratory.

Tell me about your recent participation in the 3-Minute Thesis (3MT) competition, what was that experience like?

Coming from an interdisciplinary science undergraduate program, I learned early on the importance of balancing scientific nuance and accessible language. There is a time and place to use precise jargon (as in research articles) and other times to use analogies and relatable stories (as in science media such as YouTube or Instagram). It really is an exercise in understanding who is your audience and adjusting your communication to get your point across. The 3MT competition is an excellent way to practice this skill.

I spent the beginning of my PhD in rabbit holes of literature to develop a deeper understanding of my topic. My brain was filled with jargon and technical nuance. It was an important time for me to get to the boundary of knowledge that I’m trying to break through, but I found that I began to relate less and less with people who do not similarly think about science 24/7. It’s easy to stay isolated because it’s safer than being misunderstood, but I realized that in order for my work to make a tangible impact on the world, it needs to be digested by the community-at-large and integrated into society.

This past year in my academic progress, I developed enough confidence to share my insights on my topic. At each step of the competition, I learned that confidence isn’t enough. I received feedback from the judges at the heats and semi-finals. Each perspective helped me understand that even though I can execute what I plan internally with all the necessary context conveniently in my head, it does not necessarily mean that my insights would translate perfectly through another set of ears. With the set of feedback I received, sometimes with contradictory suggestions, I was tasked to decide what to incorporate into my next talk. Even after presenting at the Finals, I can think of several things I could do to change the structure.

I still have a lot to learn on how to communicate an entire research project in three minutes. The lessons I learned from this experience are directly translatable to my other science communication efforts, in addition to other aspects of a scientific career such as in writing grant proposals. I am incredibly grateful to have this opportunity to practice these skills.

Why is science communication important to you? How does it enrich your graduate experience?

I dream of a world where literacy, and especially scientific literacy, is universal. I think if a larger and more diverse set of people learn how to digest information and think critically about what they are taking in, society might become a bit more robust if not progress exponentially.

The results and insights offered by the process of science should be equally as accessible to people as any other form of information. If a set of information is not accessible to a person, their worldview and decisions for the future become quite limited.

In a time where opinions are taken as seriously as evidence and the volume of available content is impossible for one person to fully perceive, it is so important for a person to learn what and what not to internalize into their mental model of the world.

As an openly queer person of Filipino descent, I also recognize how fortunate I am to have the education and the privilege to have the resources to develop my skills. I want to use my gifts to show the next generation of people who may relate with my identity that they too can be a scientific leader. As I carve out my niche in science, I also hope to lay a path for those with similar backgrounds as me, who may not have yet realized that their perspectives on the world are equally as valid as those who historically have dominated the podium.

Tell me a bit about your piano journey, are there any memorable experiences (i.e. playing in a band, playing for a family member) that stood out to you?

My older sister was a dancer. I remember going to her dance classes and paying attention to the piano accompanist. She died when I was 4. I think my parents knew I wanted to stay connected to music even at that young age and they enrolled me in piano lessons around that time. We did not have an actual piano for the longest time, I would practice the rudiments on a truncated organ keyboard with unweighted keys. One day a few years later while my family was at the mall, we stopped by a music store and I played a little bit on their pianos. My grandma realized I had a gift for music and that day she bought me a book of sheet music of songs from famous movies. She encouraged me to continue practicing this art and encouraged my parents to acquire a piano. Ever since then, I have refined my art and use it as a way to connect with those that I love, in whatever dimension of existence they may be in.

Does playing a musical instrument help you become a better scientist?

In many ways, science itself is an art. The process of conceptualizing a problem, understanding what needs to be done to demonstrate a theory, executing those experiments, interpreting the results, and communicating it with others to set the stage for the next problem to solve – all the parts of this process require patience, practice, and skill.

When I’m too mentally exhausted to think about complicated intermolecular forces, I can still practice this process by working on a piece of music. My process of learning a piece of music mimics how I do science. I find the sheet music (i.e. the protocol), I internalize the meaning behind the music (plan the experiments), I practice each page and experiment ways to convey the musical message (execute the experiments), then I put it together and keep it in my repertoire to share when given an opportunity (publish and present).

What is your topic of research in graduate school?

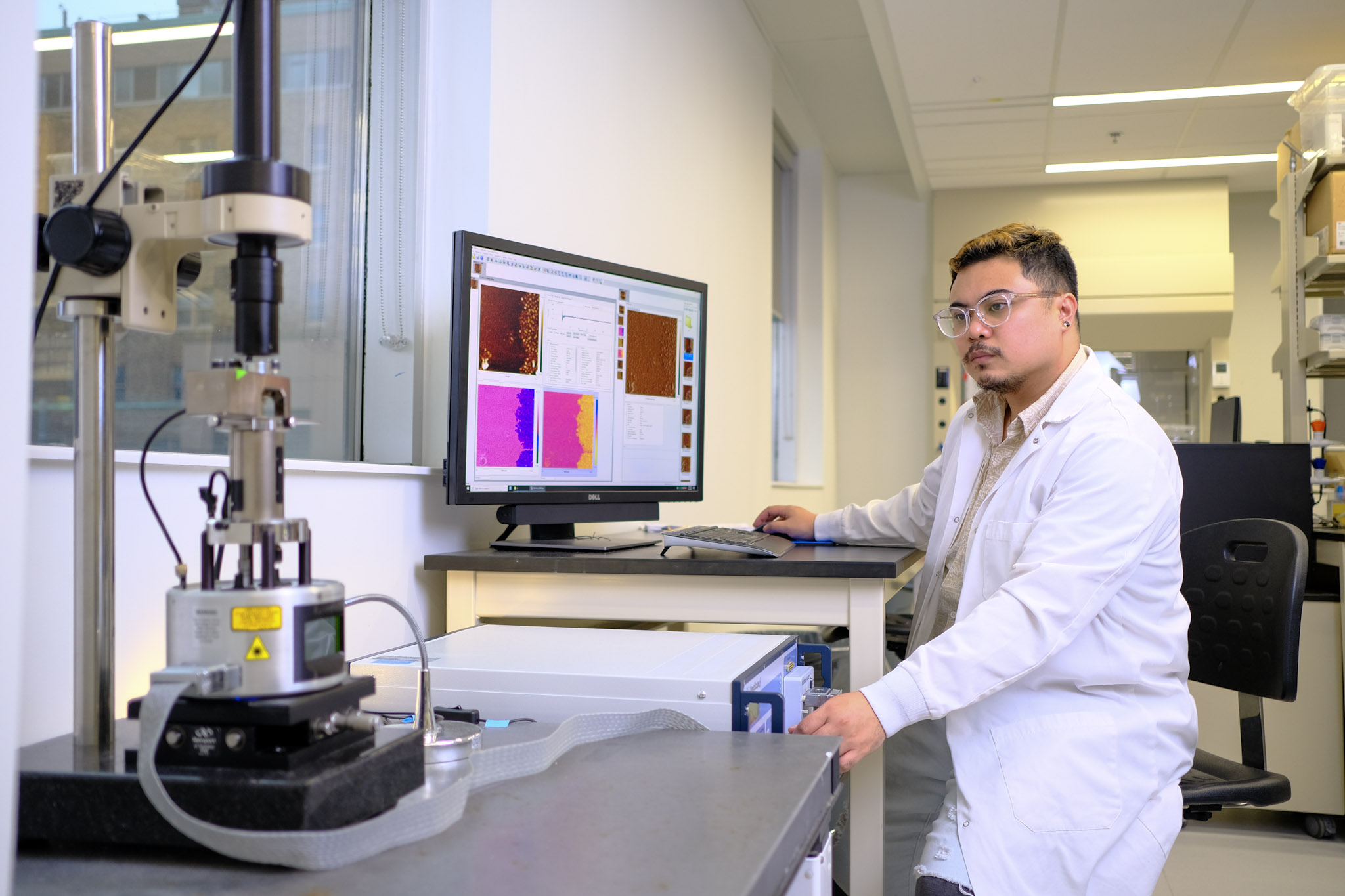

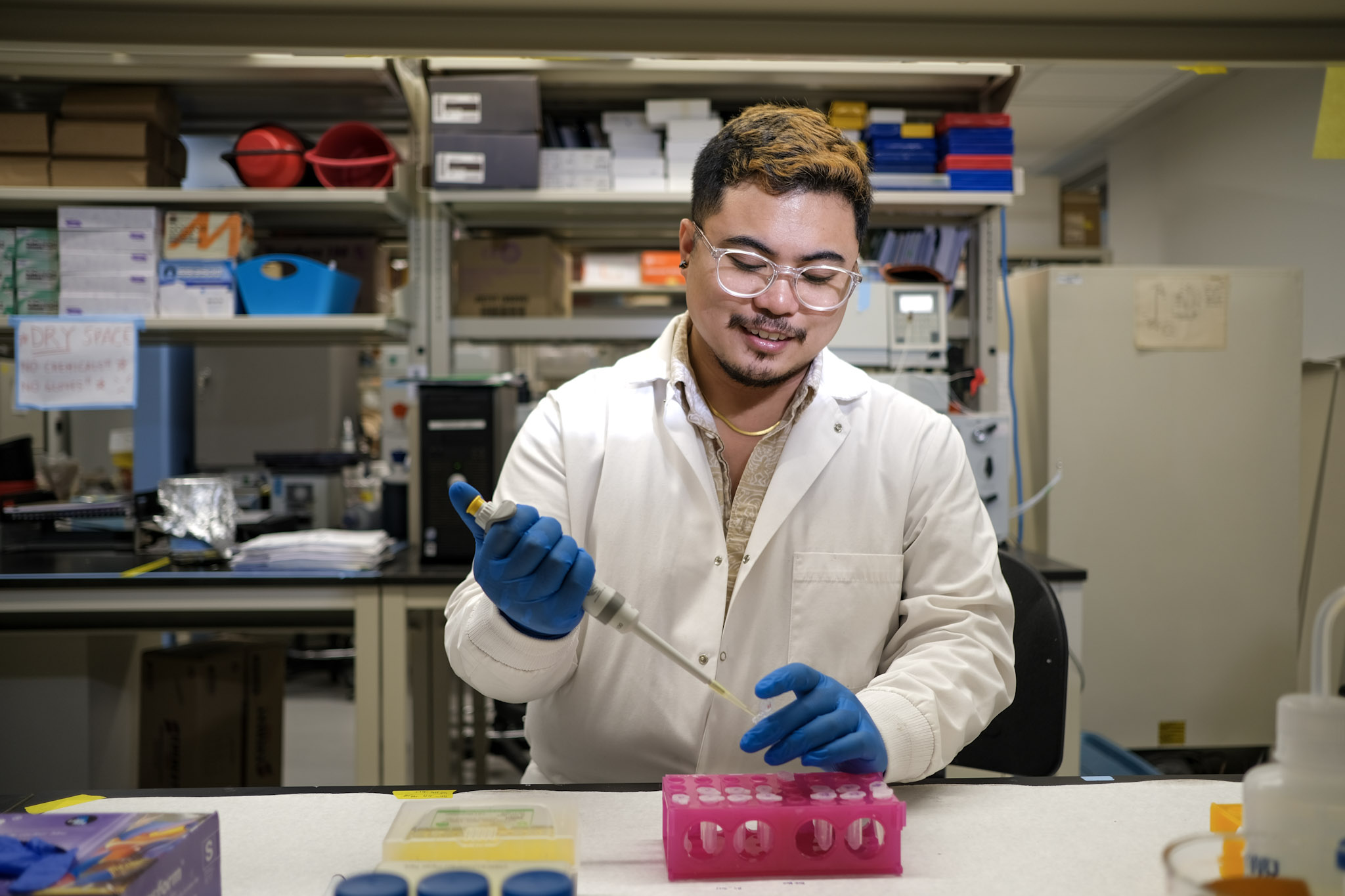

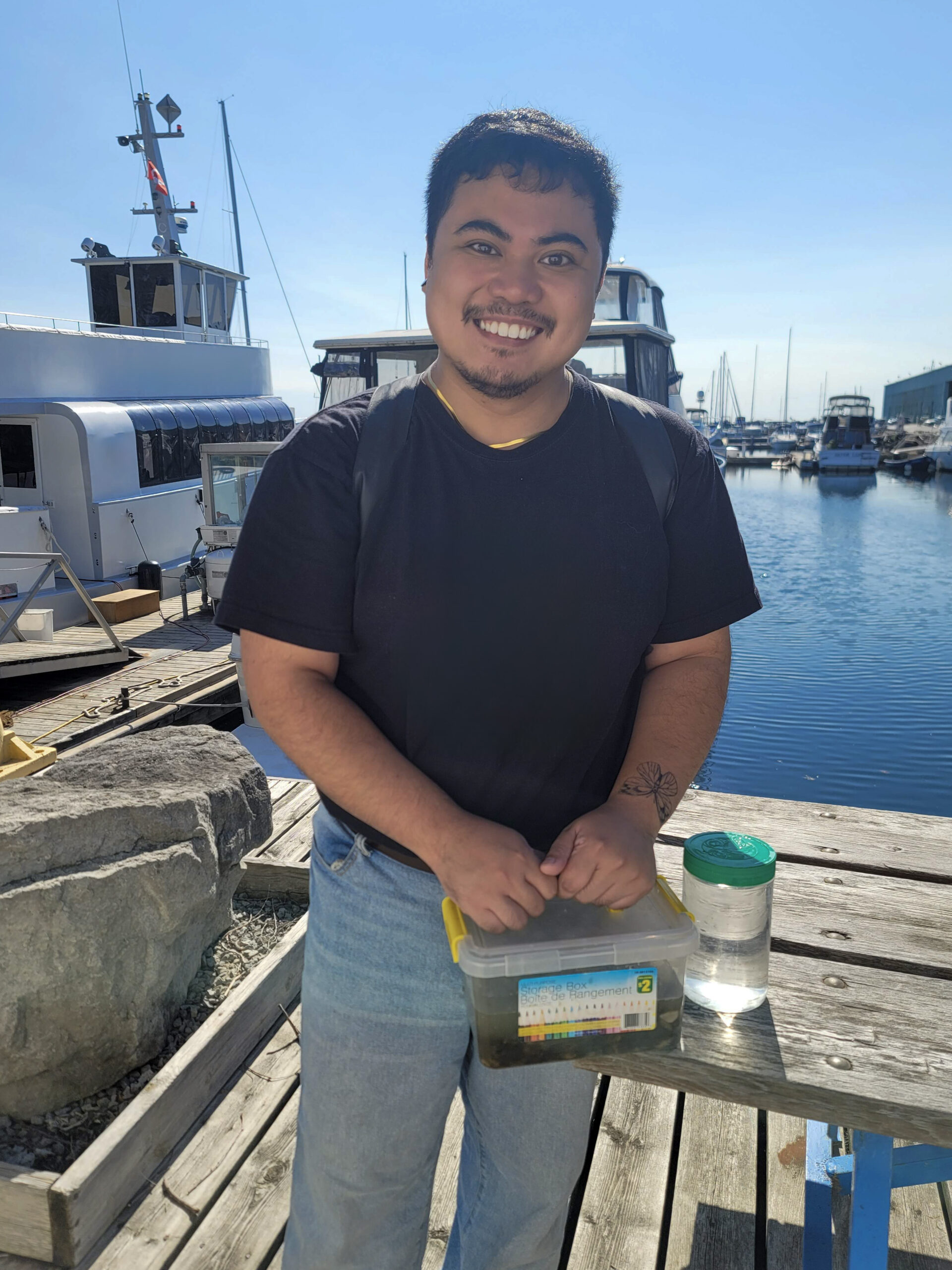

I study bioadhesion. Water is a fascinating molecule that complicates adhesive interfaces. Many tapes or glues don’t work well if the surfaces are wet. Many organisms developed a variety of ways to bypass this adhesion problem via millions of years of evolution. I’m looking to tap into that knowledge encoded in biochemistry to help design better medical adhesives. Specifically, I study the adhesive proteins of the zebra mussels and quagga mussels, notorious invasive species to North America.

Can you talk a bit about the long-term significance of this type of work?

In addition to the direct application to designing better medical adhesives, I think the whole philosophy of my research approach can be translated to many other areas. Nature truly is the world’s best engineer; knowledge and information is encapsulated in the genetic code. It is preserved and optimized over millions of years and will continue to evolve. Researchers don’t necessarily have to come up with brilliant solutions from scratch, sometimes all it takes is to walk outside, open your eyes, and look around. This kind of thinking also reflects the importance of passing down knowledge generation-by-generation by oral traditions found throughout several human cultures worldwide. It might not be enough to immortalize knowledge in books, knowledge needs to breathe in social contexts in order to be integrated and evolve.

Can you elaborate on why mental health is important for graduate students?

In graduate school, we often very quickly realize that we don’t know that much. At the individual level and as a collective, there are so many questions that are still unanswered. It can be quite exciting and motivating, but it can also be overwhelming. Entering the world of the unknown may be a novel experience for many who enter graduate school, many of whom have found success in knowing information or at least knowing that information is found somewhere. This can be quite destabilizing and it’s important to be present enough to understand the resulting cornucopia of feelings. Once you break through these feelings of despair and overwhelm, it is incredibly fulfilling and ultimately more productive to work towards your research goals.

What are some resources and tactics that helped you through tough times during graduate school?

Support and routines. I had to build and rebuild my support network and set-up sustainable routines to help me get through each day. I realized I couldn’t do this alone. Although I am responsible for my own work and progress, to do this work, I needed to have people to notice how I am doing and to give me the reality check that if I’m looking like I’m at the verge of a burnout, I need a break. This support network includes my boyfriend, my group of friends, my therapist, and my labmates and supervisory committee. The people around you generally want you to succeed. Let them help you.

Routines are so important to set-up as early as possible. It’s a common saying that graduate school “is a marathon and not a sprint”. There will be times where you need to pick up the pace and times where you have more space to breathe. If you have a good sense of baseline forward momentum, you will be able to adjust your trajectory accordingly.

For more information on my story, visit www.scientistanjo.com or

find me @ScientistAnjo on Instagram.