In a new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers in the lab of Professor Aaron Wheeler (Chemistry, IBBME) have demonstrated a novel and non-invasive way to manipulate cells through microrobotics.

Cell manipulation — which requires moving small particles from one place to another — is an integral part of many scientific endeavours. One method of manipulating cells is through optoelectronic tweezers (OET), which use various light patterns to directly interact with the object of interest.

Because of this direct interaction, there are limitations to the force that can be applied and speed in which the cellular material can be manipulated. This is where the use of microrobotics becomes useful.

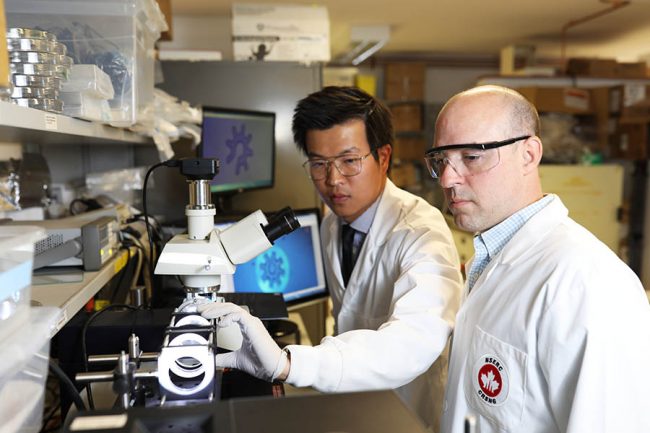

Led by postdoctoral fellow Dr. Shuailong Zhang (Chemistry) and Wheeler, the researchers have designed microrobots (working at the sub-millimetre scale) that can be operated by OET for cell manipulation.

Instead of using light to directly interact with the cells, the light is used to steer cogwheel-shaped microrobots that can “scoop up” cell material, transport it and then deliver it. This manipulation can be done at greater speeds while causing less damage to the material compared to traditional OET methods.

“The ability of these light-driven microrobots to perform non-invasive and accurate control, isolation and analysis of cells in complex biological environment make them a very powerful tool,” says Zhang.

“Traditional techniques that are used to manipulate single cells while evaluating them by microscopy is slow and tedious, requiring a lot of expertise to carry out,” says Wheeler, who is also cross-appointed to the Donnelly Centre for Cellular and Biomolecular Research.

“But these microrobots are inexpensive and very simple to use and they have a wide range of applications in the life sciences and beyond.”

In addition to cell analysis, the microrobots can also be used in cell sorting (for clonal expansion), RNA sequencing and cell-cell fusion (commonly used in the production of antibodies).

“Neural stem cells are responsive to a multitude of cues and environmental stimuli in their niche, and these change with injury, so teasing out the signals, and cell responses, is a huge challenge when we are trying to harness the potential of stem cells for neural repair,” says Professor Cindi Morshead (IBBME, Surgery), who is a co-author of the study. Her research in regenerative medicine works with neural stem cells that reside in the brain and spinal cord.

“These microrobots allow for the exquisite control of the cells and their microenvironment, tools that we will need to learn how best to activate the stem cells.”