Prof. Warren Chan (IBBME, Donnelly Centre), Dr. Samira Mubareka (Sunnybrook Hospital), Dr. Jonathan Gubbay (Public Health Ontario) and their trainees have summarized current diagnostic tools for detecting and surveilling COVID-19 in the journal ACS Nano. This article aims to guide researchers in developing COVID19 diagnostics by discussing current and emerging diagnostic tools.

“As a diagnostic developer, we were not sure where to start in the development process at the end of January. Our team of researchers thought it’s important to summarize the current state of COVID-19 diagnostics.” says Professor Warren Chan at the University of Toronto, who is currently working on diagnostic devices for infectious disease detection. “Information organized in a thorough review will better guide us in diagnostic development.”

Early detection of COVID19 is essential in managing the virus spread across Canada. This is evident by the expedition of testing kits by Health Canada, and the wide practice of hospital testing of at-risk populations.

Although symptoms for COVID19 range from coughs to severe pulmonary failures that require respirators, these symptoms do not directly suggest whether patients have the virus. Positive identification has been validated currently by performing nasal swab of suspected individuals, where they are then transported to laboratories for testing.

Once in the laboratory, researchers use a method called Reverse-Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR), to amplify miniscule amounts of viral genetic information to make them detectable. This method is currently used in a set of commercially available diagnostic kits expedited by Health Canada.

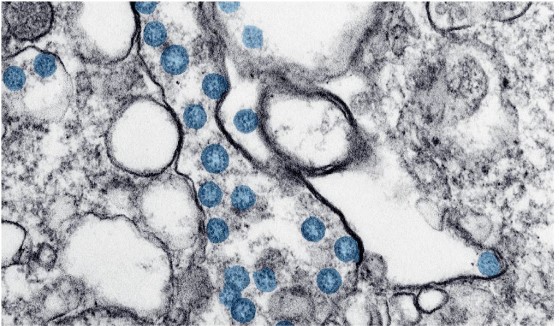

The false negatives in current COVID19 tests can severely undermine the effort of disease control by not being able to detect the virus in patients. To improve the accuracy of diagnostic testing the researchers suggest using multiplexing testing – a method that can detect multiple viral components. Some of which can be antibodies produce by the body in response to the infection, or proteins that are specific to the exterior of the virus.

Using portable diagnostic devices is another potential improvement to the current system. The virus upon extraction from a patient has to be transported to certified laboratories for testing, and this process could take up to 4 days in Ontario. The use of portable diagnostic devices could reduce the stress exerted on these laboratories and also improve result turn-around time.

The authors suggest using smart phones as an additional diagnostic tool for measuring metrics through patients self-reporting. This will better inform public health agencies about disease spread patterns, data to be linked up to data repository in the Province and Canada, and aid diagnostic and surveillance efforts. The Government of Ontario currently has a website for self-reporting for individuals who are suspect they might have the virus.

“We hope this article guides other researchers in rapidly designing COVID-19 diagnostics, so that we can curb the spread.” says Chan.